1. INTRODUCTION

The genus Paeonia L. (Paeoniaceae) includes a number of herbaceous peony species, and among them, five taxa of Paeonia were found in Serbia (Čutović et al., 2022), including Paeonia daurica subsp. daurica Andrews. In addition to being decorative, herbaceous peonies are considered important sources of crude drugs in traditional Chinese and Persian medicine (Tosun et al., 2011). In particular, their leaves, when used as a powder or macerate, have been used in cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, brain, kidney, and uterus disorders (Tahmasebi et al., 2021).

Paeonia daurica subsp. daurica Andrews is a perennial plant that grows on all continents of the northern hemisphere, including the territories of countries of the Middle (Turkey, Iran) and Far East (China, Japan) (Güner et al., 2000). Its roots are thin and resemble carrots, the leaves are made up of nine leaflets, and each stalk bears on flower, supported by one or two leafy bracts. There are several subspecies which differ in the size and shape of the leaflets, the hairiness of the carpels and the leaflets, and the color of the petals (white, pale yellow, pink, and red). P. daurica subsp. daurica is found in Serbia. Despite the use of P. daurica in disease prevention, there are only two reports on the chemical analysis of its root extracts (Monsef-Esfahani et al., 2023; Tahmasebi et al., 2021) and none on its leaf extracts, particularly on P. daurica subsp. daurica.

The flowers and roots of some members of genus Paeonia proved to be source of many beneficial components, including anthocyanins, flavonoids, tannins, stilbenes, triterpenoids, steroids, and alkaloids (Li et al., 2021). Even though chemical profiling of P. daurica is still very poor and refers only to the essential oil of its flower, leaves and stems (Tosun et al., 2011), its use in folk medicine for various disorders (epilepsy, rheumatism, cough, whooping cough, asthma, tuberculosis, gastroenteritis, colic, diarrhoea, diabetes, etc.) is well documented (Demirboğa et al., 2021; Ugulu et al., 2009).

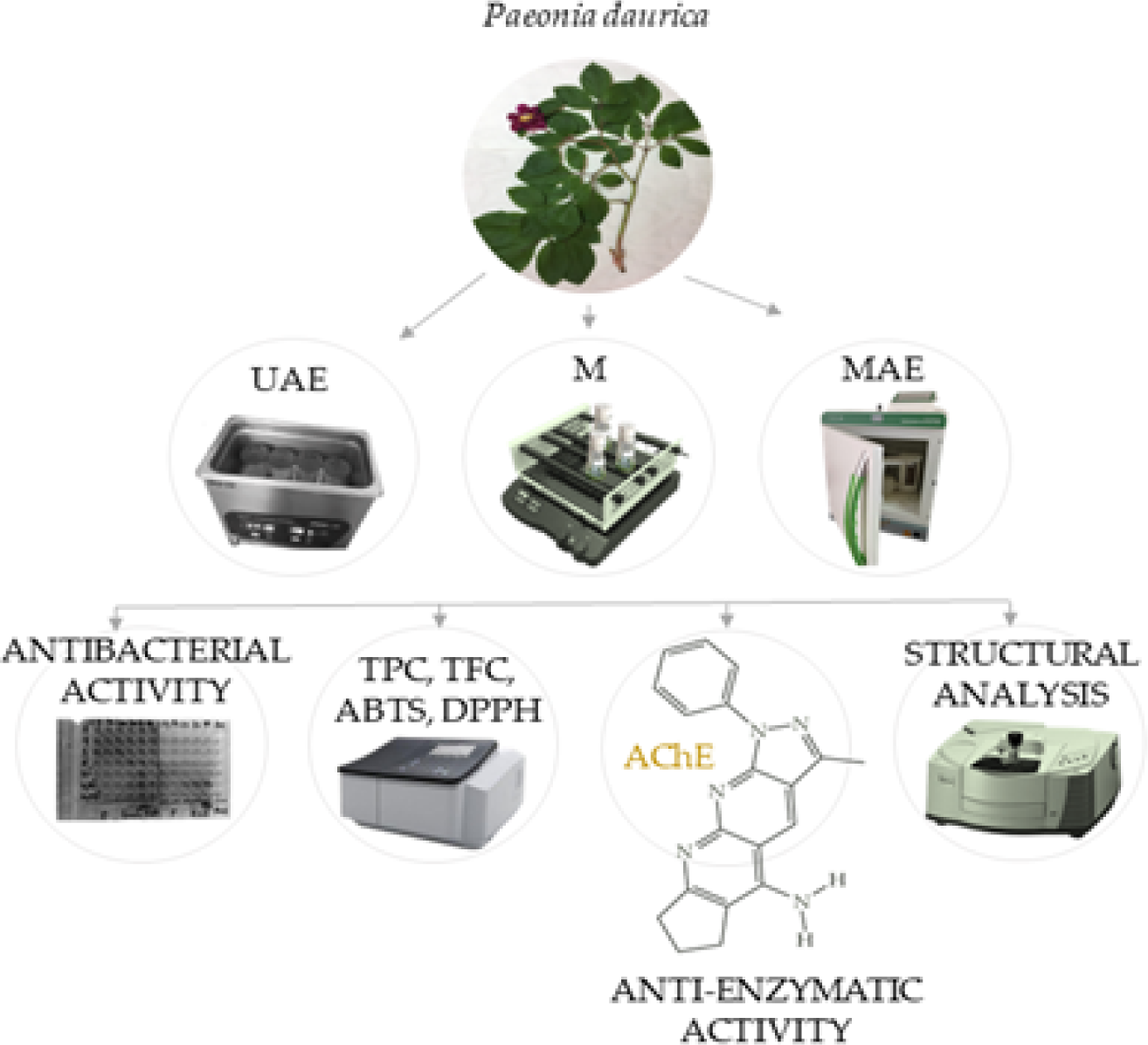

Therefore, the aim of this study was to evaluate antioxidant, antibacterial, and anti- enzymatic activities of the leaf extract of P. daurica using indirect in vitro tests, as well as to determine total phenolic and flavonoid contents and FTIR spectra. The antioxidant activity was conducted using the 2,2 ′ -azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS) and 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radical scavenging assays, the antibacterial activity was evaluated against three Gram-positive and three Gram-negative bacteria, while anti- enzymatic activity was performed against five enzymes associated with neurological, endocrinological, and skin diseases. Also, in the present study, ultrasound- (UAE) and microwave-assisted extractions (MAE) were used as highly selective and reproducible extraction techniques, in comparison to a conventional method such as maceration (M) known for its economic efficiency, in order to determine the most satisfactory method for polyphenol extraction from the leaves of P. daurica.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Plant material

The leaves of P. daurica subsp. daurica Andrews (LPD – Figure 1) were collected in May 2022, from Južni Kučaj, the mountain in Eastern Serbia (630-870 m a. s. l.). The collecting of leaves was conducted with the permission of the Government of Republic of Serbia (No. 353-01-1467/2021-04, May 26, 2022). The voucher specimen (2-1107) of this plant species was deposited in the herbarium BUNS of the Department of Biology and Ecology, Faculty of Sciences, University of Novi Sad, Serbia, where the identify confirmation was conducted.

Prior to extraction, plant material was shade dried at 21 ◦C, for 21 days. Dried leaves were grounded by a universal mill (M 20, IKA®-Werke, GmbH & Co. KG, Germany), and obtained particles were separated using a sieve of 0.5 mm.

2.2. Standards and reagents

Ethyl alcohol (96%, v/v, Zorka Pharma, Serbia) and deionized water were used as solvents. Deionized water was obtained using a Simplicity® UV water purification system (Merck Millipore, Germany). Folin-Ciocalteu’s phenol reagent (2N), gallic acid (97.5-102.5%), catechin monohydrate (≥98%), potassium hexacyanoferrate (III) (≥99%), aluminum chloride (III) (98%), sodium nitrate (≥99%), sodium carbonate (≥99.5%), sodium hydroxide (95%), 2,2’-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulphonic acid) or ABTS, 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl or DPPH, and 6-hydroxy-2,5,7,8-tetramethylchroman-2-carboxylic acid or Trolox, 5,5’-Dithiobis(2-nitrobenzoic acid), acetylcholinesterase from Electrophorus electricus (electric eel), Type-VI-S, EC 3.1.1.7, butyrylcholinesterase from equine serum, EC 3.1.1.8, acetylthiocholine iodide (AS, >99%), butyrylthiocholine chloride, kojic acid (AS, >99%), α-amylase solution (ex-porcine pancreas, EC 3.2.1.1), acarbose (>95%), p-iodonitrotetrazoliumviolet (>95%), α-glucosidase solution (from Saccharomyces cerevisiae, EC 3.2.1.20), Lugol reagents (diluted iodine-potassium iodide solution), and formic acid (98-100 %, HPLC grade), were obtained by Sigma Aldrich, Germany. Potassium persulfate (≥99%) was purchased from Centrohem, Serbia.

2.3. Preparation of the extracts

The extracts of LPD were prepared using UAE, M, and MAE; each extraction protocol is described below in the individual section. The schematic view of the experiment is presented in Figure 2.

2.3.1. Ultrasound-assisted extraction (UAE)

UAE was performed using the digital ultrasound bath (DU-32, ARGO LAB, Italy) with a frequency of 35 kHz at room temperature (25 ± 5 ◦C). The time of the extraction was 15 min, the concentration of ethyl alcohol was 50% while the solid-to-solvent ratio was 1:10. After extraction, the extract was filtered through the cellulose acetate filter (0.2 μm) and stored at 4 ◦C until further analysis.

2.3.2. Maceration (M)

Maceration was carried out on the tube roller mixer (Stuart SRT6, Germany) at room temperature (25 ± 5 ◦C). The duration of extraction was 15 min, solid-to-solvent ratio was 1:10, temperature of 100 ◦C, while the concentration of ethyl alcohol was 50%. After maceration, the extract was filtered through the cellulose acetate filter (0.2 μm) and stored at 4 ◦C until further analysis.

2.3.3. Microwave-assisted extraction (MAE)

MAE was carried out using a microwave device (Milestone ETHOS X, Italy), equipped with a 2.45 GHz reactor and two 2 magnetrons achieving a maximum operative power of 1.8 kW. All tests were conducted at the normal atmospheric pressure in SR-15 rotor segment containing a high-density polypropylene mold with a modified poly(tetrafluoroethylene) vessel, cover and stirrer bar. The time of extraction was 2 min, solid-to-solvent ratio was 1:10, temperature of extraction was 100 ◦C, while the concentration of ethyl alcohol was 50%. After extraction, the extract was filtered through the cellulose acetate filter (0.2 μm) and stored at 4 ◦C until further analysis.

2.4. Total polyphenol content (TPC)

TPC was determined using the modified Folin-Ciocalteu method (Čutović et al., 2022). The extract (0.02 mL) was added to deionized water (1.5 mL) and mixed with Folin-Ciocalteu phenol reagent (0.1 mL). Subsequently, sodium carbonate solution (0.3 mL, 20%, w/v) was added and mixture was made up to 2 mL with deionized water. Then, the mixture was left in the dark at room temperature for 120 min. The absorbance was read at 765 nm against blank solution (all reagents except the extract) on the UV-Vis scanning spectrophotometer (UV/Vis 1800, Shimadzu, Japan). Gallic acid (GA) was used as a standard for construction of the calibration curve. The TPC was expressed as milligrams of gallic acid equivalents per milliliter of extract (mg GAE/mL).

2.5. Total flavonoid content (TFC)

The modified aluminum chloride colorimetric method of Čutović et al. (2022) was used to estimate the TFC in extract of LPD. In short, 0.25 mL of extract and 0.75 mL of sodium nitrite (5%, w/v) were mixed with 1.25 mL of deionized water. The solution was incubated in dark for 6 min at room temperature (25 ± 5 ◦C). Then, the mixture was treated with 0.15 mL of aluminum chloride (10%, w/v) and 0.5 mL of sodium hydroxide (1 mol/L) before being topped off to a volume of 3 mL. The mixture was vortexed and kept in the dark for 30 min. The absorbance was read at 425 nm against blank solution (all reagents except the extract). Catechin hydrate (CA) was used as a standard for construction of the calibration curve. The TFC was expressed as milligrams of catechin hydrate equivalents per milliliter of extract (mg CAE/mL).

2.6. Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR)

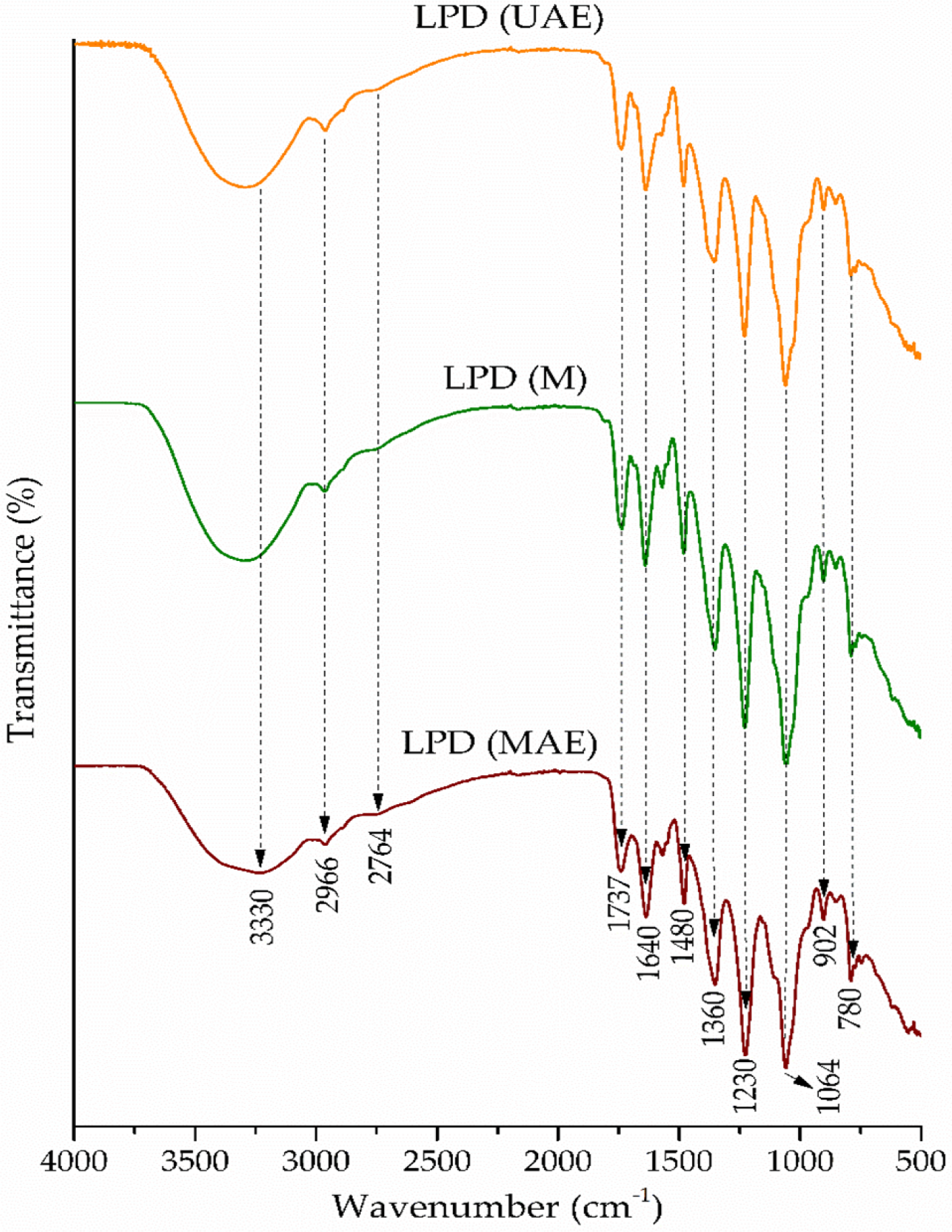

FTIR spectra of extracts of LPD were performed to identify the present characteristic functional groups. The spectra were recorded using IR-spectrometer (NicoletTM iSTM, USA) in the wavenumber range between 4000-500 cm-1, and resolution of 4 cm-1 (25 ± 5 ◦C). The analysis was performed on dry extracts, previously prepared using a Rotary vacuum evaporator (Rotavapor Heidolph 4001-efficient, Heidolph Instruments, Germany) under pressure of 0.5 bar at 25 ± 5 ◦C. Test was performed by fixing a small amount of dry extract (20 mg) to the metal chassis of the IR-spectrometer equipped with diamond crystal. FTIR spectra were processed using OMNICTM software (Thermo Fischer Scientific, USA). The graphical view of results was generated by ORIGINTM software (Origin 9.0., OriginLab, USA).

2.7. Antioxidant activity

2.7.1. ABTS assay

The ABTS assay is based on the reduction of ABTS•+ free radicals by antioxidants from the extract. The analytical protocol was defined by Čutović et al. (2022). The ABTS•+ solution (7.8 x 10-3 mol/L) was prepared by dissolving 0.02 g ABTS in 5 mL of deionized water and then adding 0.088 mL of potassium persulfate (2.45 x 10-3 mol/L). Prior to its use, the ABTS•+ solution was stored for 16 h at 4 ◦C to complete the reaction and to activate the radicals. Following activation, the ABTS•+ solution was diluted by ethyl alcohol yielding an absorbance of 0.70 ± 0.02 at 734 nm. The main solution was prepared by mixing 2.8 mL of ABTS•+ solution with 0.2 mL of extract, while the blank was prepared by mixing of the same amount of mL of ABTS•+ solution with 0.2 mL of ethyl alcohol (50%, v/v). After 30 min of incubation, the absorbance was read and the radical scavenging activity (SAABTS ) was calculated according to the Equation 1: (1) where Aco represents the absorbance of ABTS•+ solution, while Asa is the absorbance of ABTS•+ solution and the extract. Trolox was used as a standard for the calibration curve. The SAABTS was expressed as μmol Trolox equivalents per mL of extract (μmol TE/mL).

2.7.2. DPPH assay

The antioxidant activity of the extract was determined via hydrogen donating or radical scavenging ability using the stable DPPH• radicals (Čutović et al., 2022). The DPPH solution was made by dissolving 0.252 mg of DPPH in 9 mL of ethyl alcohol. The main solution was prepared by mixing 2.8 mL of DPPH• solution with 0.2 mL of extract, while the blank was ethyl alcohol. The absorbance readings were taken after 30 min against the blank at 517 nm. The scavenging radical activity (SADPPH ) was calculated according the Equation 2: (2) where Aco represents the absorbance of DPPH• solution, while Asa is the absorbance of DPPH• solution and the extract. The results were expressed as the concentration of extract required to neutralize 50% of DPPH• (IC50, mg/mL).

2.8. Antibacterial activity

Minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) and minimal bactericidal concentration (MBC) of extract of LPD were determined by microdilution method. All of the extracts of LPD were dissolved in ethyl alcohol (30%, v/v) to prepare the extract stock solution with the concentration of 10 mg/mL. The MIC and MBC values were evaluated by serial sub-cultivations of 0.01 mL of extract into microtiter plates containing 0.1 mL of broth per well and further incubation for 24 h at 37 ◦C; the values were detected following the addition of 0.04 mL of p-iodonitrotetrazolium violet (0.2 mg/mL) and incubation at 37 ◦C for 30 min, as previously described by Nikolić et al. (2014). The lowest concentration of extract of LPD without any visible growth of microbial strains was taken as MIC value, while the MBC shows the lowest extract concentration at which the initial inoculum was killed by 99.5%. The antibacterial activity was examined against three Gram-positive (Listeria monocytogenes NCTC 7973, Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 11632, and Bacillus cereus human isolate) and three Gram-negative (Salmonella typhimurium ATC 13311, Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853, and Escherichia coli ATCC 25922) bacterial strains. The bacterial strains were gained from the Collection of the Department of Plant Physiology, University of Belgrade, Institute for Biological Research “Siniša Stanković”, Belgrade, Serbia. Fresh overnight cultures of all bacterial strains were adjusted with sterile saline to a concentration of 1.0 x 106 CFU (colony-forming unit) per well.

2.9. Determination of enzyme inhibitory effects

For the determination of anti-enzymatic activity, all of the dry extracts of LPD were dissolved in ethyl alcohol (30%, v/v) in order to prepare the stock solution with concentration of 10 mg/mL. The inhibitory effects of extracts of LPD were investigated against cholinesterases (acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase (associated with Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s diseases)), amylase and glucosidase (both related with diabetes mellitus type 2) and tyrosinase (associated with skin melanoma).

2.9.1. Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) and butyrylcholinesterase (BChE) enzymatic assays

The AChE and BChE inhibitory activities of the extracts of LPD was accessed following instructions given by Sut et al. (2019). In short, 0.025 mL of extract of LPD (1 mg/mL) was combined with 0.125 mL of 5,5’-dithiobis (2-nitrobenzoic acid) and 0.025 mL of AChE, or BChE in tris-hydrochloride buffer solution (1 mol/L, pH 8.0) in a 96-well microplate and incubated for 30 min at 25 ◦C. The absorbances were read at 405 nm. Standard inhibitor for cholinesterase’s was galantamine. Results were quantified by subtracting the absorbance of the control probe from that of the test solution and expressed as milligrams of galantamine equivalents per gram of extract (mg GALAE/g). A control was prepared by adding the test solution to all reagents without an enzyme.

2.9.2. Enzymatic assay of α-amylase and α- glucosidase

The α-amylase enzymatic assay was performed as carried out following the instructions given by (Sut et al., 2019). In brief, 0.05 mL of extract of LPD (1 mg/mL) was mixed with the α-amylase solution (ex-porcine pancreas) in phosphate buffer (6 x 10-3 mol/L) in a 96-well microplate and incubated for 10 min at 37 ◦C. The reaction was initiated by adding of 0.05 mL of starch (0.05%, w/v). A control was made by adding the test solution to all reagents without enzyme. Then, the mixture was thermostated for 10 min at 37 ◦C, after which 0.025 mL of hydrochloric acid (1 mol/L) and 0.1 mL of iodinepotassium iodide (Lugol’s reagent) were added to end the process. The absorbances were read at 630 nm. Also, the absorbance of the control was subtracted from that of the extract and the α-amylase inhibitory activity was expressed as millimoles of acarbose equivalents per gram of extract (mmol ACAE/g). On the other hand, the α-glucosidase inhibitory activity was carried out as follows: 0.05 mL of the extract of LPD (10 mg/mL) was mixed with a 0.05 mL of glutathione and 0.05 mL of α-glucosidase solution in phosphate buffer (1 mol/L, pH 6.8) in 96-well microplate, and incubated for 15 min at 37 ◦C. A blank was prepared by adding the test solution to all reagents without adding enzyme. Then, the reaction was ended by adding 0.05 mL of disodium carbonate (0.2 mol/L). The absorbances were read at 400 nm, while the α-glucosidase inhibitory activity was expressed as millimoles of acarbose equivalents per gram of extract (mmol ACAE/g).

2.9.3. Enzymatic assay of tyrosinase

Tyrosinase inhibitory activity was conducted following the experimental protocol provided by Mocan et al. (2017). Specifically, 0.025 mL of the extract of LPD (1 mg/mL) was mixed with 0.04 mL of tyrosinase and 0.01 mL of phosphate buffer (1 mol/L, pH 6.8) in a 96-well microplate and incubated for 15 min at 25 ◦C. Then, the reaction was initiated with the addition of 0.04 mL of L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine. A control was prepared by adding the test solution to all reagents without enzyme. The absorbances of the sample and control were recorded at 492 nm after 10 min of incubation at 25 ◦C. Tyrosinase inhibitory activity was calculated by subtracting the absorbance of the control from that of the test solution and expressed as milligrams of kojic acid equivalents per gram of extract (mg KAE/g).

2.10. Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was conducted by using the analysis of variance (one-way ANOVA) followed by Duncan’s post hoc test, within the statistical software STATISTICA 7.0. The differences were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05, n=3.

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The extracts of LPD, obtained by UAE, M, and MAE were analyzed via TPC, TFC, ABTS- and DPPH radical scavenging activity. The TPC and TFC, with GA and CA as the referent standards, are shown in Table 1, while the results of ABTS and DPPH radical scavenging activities are shown in Table 2. All extracts were analyzed in term of structural properties (FTIR), as well as the antibacterial and anti-enzymatic activities.

| Extraction method | TPC [mg GAE/mL] | TFC [mg CAE/mL] |

|---|---|---|

| UAE | 1968.88 ± 112.34 b | 1062.67 ± 87.76 a |

| M | 2151.38 ± 134.11 a | 1031.00 ± 69.99 a |

| MAE | 2141.38 ± 105.97 a | 1096.00 ± 98.97 a |

GAE: gallic acid equivalent; CAE: catechin equivalent; UAE: ultrasound-assisted extraction; M: maceration; MAE: microwave-assisted extraction; values with the same letter in each showed no statistically significant difference (p > 0.05, n = 3, one-way ANOVA, analysis of variance, Duncan’s post hoc test).

| Extraction method | ABTS [μmol TE/mL] | DPPH IC50 [mg/mL] |

|---|---|---|

| UAE | 0.2628 ± 0.09 a | 0.051 ± 0.01 b |

| M | 0.2631 ± 0.12 a | 0.046 ± 0.02 a |

| MAE | 0.2634 ± 0.09 a | 0.048 ± 0.02 ab |

TE: Trolox equivalent; DPPH IC50: the concentration of the extract required to neutralize 50% of DPPH•; UAE: ultrasound-assisted extraction; M: maceration; MAE: microwave-assisted extraction; values with the same letter in each showed no statistically significant difference (p > 0.05, n = 3, one-way ANOVA, analysis of variance, Duncan’s post hoc test).

3.1. Total polyphenol and flavonoid contents of the extracts

TPC was significantly higher in the extracts obtained by M and MAE compared with those obtained by UAE, while the results obtained by M and MAE were similar to each other (Table 1). Although the literature showed the advantages of UAE, including high extraction yield, quality of extract, better kinetics, lower price, simplicity, and employment of a wide range of mediums (Lee et al., 2013), the results from this research suggest that the UAE method (performed in an ultrasound bath) provided lower values of TPC compared to the M and MAE procedures. The potential explanation could be that the excessive amount of plant material (a ratio of 1:10) causes the drastic increase in viscosity and inhibits the expansion of ultrasound waves, as well as the diffusion of polyphenol compounds (Vuleta et al., 2012). The results of TPC are in accordance with the previously published papers, where higher temperatures (implemented during MAE) had a strong influence on the polyphenols extractability in waterethyl alcohol extracts of medicinal plants (Dent et al., 2013; Miron et al., 2011). This phenomenon could be explained by the fact that high temperature during MAE decreases the viscosity of the solvent, assisting its penetration through the plant tissue which causes the more intensive dissolution of bioactive molecules and accelerates mass transfer. In addition, some reports suggest that increment of solvent temperature (which is the case during MAE) could decrease the surface tension and consequently enhance the wetting and swelling of plant material resulting in more efficient extraction (Vergara-Salinas et al., 2012). Moreover, some findings suggest that temperatures were the dominant factor in maximizing the values of TPC in numerous plant extracts (Hossain et al., 2011). The results of TFC show different trend. Namely, the highest TFC was observed in extracts of LPD obtained by MAE, followed by UAE and M, but differences were not significant.

These results are in agreement with those published earlier by other researchers (Jovanović et al., 2022; Nayak et al., 2015). In fact, the high efficiency of MAE is based on the following phenomenon - that rapid heating of the solid content and solvent creates a high vapor pressure of free aqueous molecules in the plant material, which disrupts the cell wall and accelerates the release of the content into the surrounding extraction medium. On the other hand, during UAE, solid and liquid phases were vibrated and accelerated, the intramolecular forces are not able to hold the structure of molecule in the intact state, so the formed bubbles can produce mechanical effect which results in cell disruption of biological membranes of plant tissue (Batinić et al., 2022). However, M also provided a higher flavonoid yield confirming that flavonoids are thermosensitive compounds that can be degraded by microwaves and ultrasound waves.

3.2. FTIR study

The FTIR analysis was used to identify the presence of specific functional groups of LPD obtained by the UAE, M, and MAE methods. The FTIR spectrum of extracts of LPD is shown in the Figure 3. As can be seen from the adsorbent spectrum, the modest adsorption at 3330 cm-1 occurs as a result of the O-H stretching from both hydroxyl and phenolic groups (Lee et al., 2009). The adsorption at 2966 and 2764 cm-1 is due to the C–H stretching vibrations originating from =CH2/R−O−CH3/−CH3 groups (Lee et al., 2009; Oancea et al., 2021). A band at 1737 cm-1 indicates the presence of C=O vibration originating from carboxylic and ester functionalities (Lazzari et al., 2018). The broad band at 1640 cm-1 is mainly attributed to the C–H bending vibrations of the aromatic structure (Geng et al., 2016). A peak around 1480 cm-1 originated from the C-H stretching vibration and O−C−H in plane bending and has been associated with the phenyl core of phenolic acids. The band at 1360 cm-1 originated from the O−H bending modes in gallic acid derivatives (Oancea et al., 2021). Vibration at 1230 cm-1 is attributed to the C−O stretching modes of aromatic alcohols, while the strong absorption at 1064 cm-1 occurs as a result of C−O−C asymmetric stretching vibrations derived from primary alcohols in gallic acid derivatives (Lazzari et al., 2018).

3.3. Determination of antioxidant activity

The antioxidant activity of extracts of LPD was examined via analyzing ABTS•+ scavenging potential and through the ability of tested extract to donate 1H, using the stable DPPH• (Čutović et al., 2022).

According to the results from the ABTS assay, the highest antioxidant activity was achieved in the extract of LPD obtained using MAE method, followed by M and UAE, but the differences were not significant (Table 2). In global, the antioxidant activity has arisen from the content of some representatives of polyphenols, such as gallic acid, quercetin, isorhamnetin, and similar (Miraj et al., 2016). As mentioned, the extract of MAE was the most potent probably due to the strong interaction of microwaves with molecules of the solvent, resulting in increase of internal temperature and pressure within plant material, facilitating the breakage of the cell wall and delivering bioactive molecules in the extraction medium.

The results of DPPH radical scavenging activity differ from those obtained by ABTS (Table 2). The highest antioxidant activity (the lowest IC50) was found in the extract of LPD obtained by M, followed by MAE and UAE. This result is partially in agreement with previously published paper of Jovanović, Ðorđević, Zdunić, Pljevljakušić, Šavikin, Gođevac and Bugarski (2017). Namely, the high temperatures during MAE favor the degradation of polyphenols (Burns et al., 1999). Moreover, in some literature reports it can be found that extended time of sonication could also damage extracted natural antioxidants and degrade extracts quality, due to the generation of reactive oxygen species by ultrasound waves (Jovanovic, Petrovic, Ðordjevic, Zdunic, Savikin and Bugarski, 2017).

3.4. Determination of antibacterial activity

The results of the antibacterial activity evaluated by the microdilution method are summarized in Table 3. The three different extracts (UAE, M, and MAE) of LPD originating from Južni Kučaj were all tested for their antibacterial activities against six bacterial strains. The extracts of LPD were assessed as a potential source of antibacterial agents intended for application in the human GI against different pathogens. The extracts of LPD had the highest antibacterial activity against P. aeruginosa, while other extracts did not differ visibly in term of inhibition of bacterial growth. The extraction procedure proven to produce the most potent antibacterial agents is M, followed by UAE and MAE. In fact, according to Fick’s second law of diffusion, the quantity of extracted polyphenols, the carriers of antibacterial activity, will be proportionally enhanced due to the extension of the extract time (Jovanovic, Petrovic, Ðordjevic, Zdunic, Savikin and Bugarski, 2017). Previous investigations on this theme have shown that the leaves of P. daurica have strong antibacterial effects against some Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, such as S. aureus, L. monocytogenes, P. aeruginosa and E. coli (Tosun et al., 2011). It can also be found that the alcoholic extract of different organs of P. daurica subsp. tomentosa has strong antibacterial potential against S. aureus and E. coli (Mahdavi Fikejvar et al., 2018).

| Extraction method | Salmonella typhimurium | Listeria monocytogenes | Bacillus cereus | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Staphylococcus aureus | Escherichia coli | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIC | MBC | MIC | MBC | MIC | MBC | MIC | MBC | MIC | MBC | MIC | MBC | |

| UAE | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0.5 | 1 |

| M | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 |

| MAE | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

UAE: Ultrasound-assisted extraction; M: Maceration; MAE: Microwave-assisted extraction; MIC: Minimal inhibitory concentration; MBC: Minimal bactericidal concentration.

3.5. Determination of anti-enzymatic activity

3.5.1. The inhibitory activities of AChE and BChE

One of the most widely employed therapeutic agents for treating the symptoms of Alzheimer’s (AD) and Parkinson’s diseases (PD) are cholinesterase inhibitors (Sut et al., 2019). Specifically, the neurological theories indicate that acetylcholine, a neurotransmitter that appears to play a crucial role in memory, is deficient in the neocortex or hippocampal regions of the brain and is responsible for at least some of the cognitive impairment observed in AD and PD patients. This hypothesis is especially gaining importance in the late AD and PD stages when levels of AChE have declined by up to 85% so that the BChE, becomes main cholinesterase in the brain (Loizzo et al., 2008). Results from this study suggest that an extract of LPD can be selected as the most promising candidate for treating the previously mentioned neurodegenerative disorders. As can be seen from Table 4., all tested extracts of LPD had the same effect on the AChE, while the extract of LPD obtained by MAE had the greatest effect on the BChE. The substantial inhibitory effect observed in the tested extracts can be attributed to the noncovalent interactions between paeoniflorin from LPD and macromolecular receptors presented in both enzymes (Montanari et al., 2019).

| Extraction method | AChE inhibition | BChE inhibition | Amylase inhibition | Glucosidase inhibition | Tyrosinase inhibition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [mg GALAE/g] | [mmol ACAE/g] | [mg KAE/g] | |||

| UAE | 1.89 ± 0.01 a | 0.96 ± 0.05 b | 0.25 ± 0.00 a | 1.07 ± 0.00 a | 51.00 ± 1.18 a |

| M | 1.88 ± 0.09 a | 0.84 ± 0.04 a | 0.28 ± 0.02 b | 1.09 ± 0.00 b | 50.08 ± 0.83 a |

| MAE | 1.89 ± 0.02 a | 0.97 ± 0.08 b | 0.33 ± 0.00 c | 1.09 ± 0.00 b | 53.92 ± 0.53 b |

GALAE: galantamine equivalents; ACAE: acarbose equivalents; KAE: kojic acid equivalents; AChE: acetylcholinesterase; BChE: butyrylcholinesterase; Values with the same letter in each column showed no statistically significant difference (p > 0.05; n = 3, one-way ANOVA, analysis of variance, Duncan’s post hoc test).

3.5.2. The inhibitory activities against α-amylase and α-glucosidase

Hyperglycemia represents a risk factor in the development of diabetes mellitus type 2 (DM), so the control of glucose levels in serum is crucial in the early treatment of this disease and in further decreasing of the incidence of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular complications (Inzucchi, 2002). Salivary amylase and intestinal glycosidase are the key enzymes in the digestion of dietary carbohydrates. Their inhibitors are effective in retarding glucose absorption and suppression of hyperglycemia (Ramkumar et al., 2009). Also, acarbose (a commercially available drug) inhibits α-glycosidase in the epithelium of the small intestine, which directly influences the decrease of postprandial hyperglycemia and improves the impaired metabolism of glucose without promoting the secretion of insulin (Ramkumar et al., 2009). In this study, noticeable α-amylase and α-glucosidase inhibitory activity of LPD obtained by the MAE method was observed. Previous reports already suggested individual polyphenols (ellagic acid) or classes of polyphenols (anthocyanins) in the herbal extracts responsible for the inhibition of activities of α-amylase and α-glucosidase (Mai et al., 2007; Matsui et al., 2001). However, to create novel medications for the management of DM and its complications, the isolation of specific active principles is required.

3.5.3. The inhibitory activity against tyrosinase

Tyrosinase is a key enzyme in synthesis of melanin and the major therapeutic target to slow/mitigate the unusual darkening of the skin, i.e., cutaneous hyperpigmentation (Sut et al., 2019). Regarding tyrosinase inhibitory potential, the best activity was achieved in extracts of LPD obtained by MAE, at 53.92 mg KAE/g. This anti-enzymatic potential might be associated with the higher concentration of polyphenols in the extracts of LPD. To support this claim, Kim and Uyama (2005) found that some phenolic compounds, such as kaempferol and chlorogenic acid could chelate Cu2+ in the flexible active sites of tyrosinase, causing the inhibition of the enzyme. Also, results from this study corroborate earlier reports that some phenolic and flavonoid compounds can inhibit tyrosinase activity (Abdul Karim et al., 2014; Zamani and Gazali, 2015).

4. CONCLUSION

This study was the first attempt to evaluate the biological activities of leaf extracts of P. daurica originating from Serbia which are obtained by different extraction methods. As the research showed, the activities of the extracts varied depending on the employed methods of extraction. Namely, the maximal TPC was detected when M and MAE were used as extraction techniques, while the maximal TFC was obtained when MAE was employed. Considering the results of antioxidant activity, the highest anti-DPPH potential was achieved in the extracts of LPD obtained by M. The analysis of antibacterial activity suggests that the highest potential to inhibit bacterial growth was achieved in the extracts obtained by M, against P. aeruginosa. The research also showed that extracts of LPD, obtained by MAE had the greatest effect on the both AChE and BChE enzymes. Furthermore, the extracts of LPD obtained by MAE showed similar effects on both enzymes associated with the onset of diabetes mellitus type 2. Also, the highest tyrosinase inhibitory activity was achieved in the extracts obtained by MAE. Therefore, the M and MAE proved to be the most favorable extraction procedures used to produce extracts of LPD with wide a range of therapeutic activities related to human health. Finally, the extracts of LPD could be used as effective functional ingredients/supplements in food and pharmaceutical products, as they possess prominent antioxidant, antibacterial, and anti-enzymatic activities.